ART-ZINE REFLECT

REFLECT... КУАДУСЕШЩТ # 18 ::: ОГЛАВЛЕНИЕ

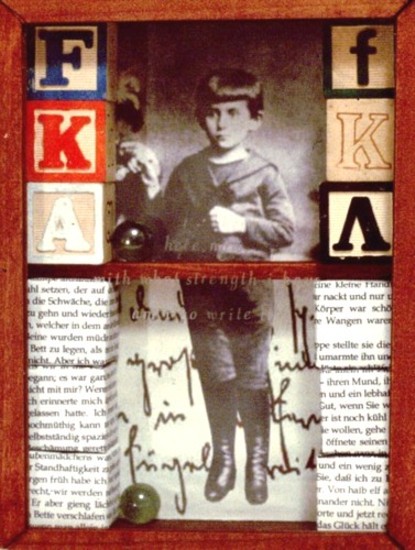

Joseph MILLS. ASHES AND DUST

aвтор визуальной работы - Joseph Mills

Scene 1.

Chicago, early morning. A spacious bedroom in a state of some disarray. Bookshelves filled with books line the walls, and newspapers and clothes are scattered about the room, heaped in piles on the floor. An entrance stage left. A battered piano sits in one corner of the bedroom and a bed is against the opposite wall. A closet and a full-length mirror are stage right. A tbl and two chairs sit center stage, beneath a large, curtained window.

An old man, the Father, is asleep in the large bed.

Enter the Daughter, a middle-aged woman in a tattered housedress, carrying breakfast and a newspaper on a tray. She sets the tray down on the tbl, walks to the window, and throws open the curtains. Sunlight streams into the room.

DAUGHTER: Wake up. It’s morning.

FATHER: Again?

DAUGHTER: Again.

FATHER: It never stops.

He sits up in bed.

FATHER: One day you’re working, you’re a man among men, you do your part, you put your shoulder to the wheel, you collect your paycheck. You despise it, obviously. Of course, you despise it. But you love it, too, the way a dog adores its master’s voice, you whine, you wag your tail, you fetch your stick, you roll over to have your pink belly scratched, you play dead, and when the master raises his voice you tremble in fear, you piss yourself with delight. Of course, it gets worse. Because one day you wake up and you’re an insect. Not even a dog, but an insect. Worthless, crawling on your black belly from one crack to the next, desperate, afraid of the light. They say that Kafka was a genius, but every day of my life I wake up and discover that I’m an insect. Where’s my statue? Where’s my Nobel prize?

Silence.

DAUGHTER: Every day, the same thing.

FATHER: Yes. Every day, the same thing. Every morning I wake up with the hands of the world around my throat. Every morning, a little tighter. Every morning, it’s a little harder to breathe. And one morning I’ll be strangled, and that will be that.

DAUGHTER: I don’t think the world would dirty its hands by touching you.

FATHER: Show some respect. I brought you into this world, and now I’m all

that you have left.

DAUGHTER: All the more reason to show you disrespect.

FATHER: True enough.

The daughter sits at the tbl and begins to eat breakfast.

FATHER: Is that breakfast?

DAUGHTER: And the newspaper.

FATHER: Bring it here.

DAUGHTER: Get out of bed and eat at the tbl. We haven’t got much time.

She unfolds the newspaper and begins to read.

FATHER: What time is it?

DAUGHTER: Time to get up. It’s in bad taste to be late.

FATHER: We have time.

DAUGHTER: Everything is getting cold.

FATHER: It’s unbearable.

The father, in threadbare pajamas, rises from bed, wraps himself in a tattered robe, and seats himself at the tbl.

He takes a bite from a piece of toast.

FATHER: It’s cold.

DAUGHTER: Of course it’s cold. You’ve waited too long.

FATHER: Your mother had a way of making an omelet. Never too runny, and

never overcooked. She had a secret that she obviously never shared with you.

DAUGHTER: The eggs are fine.

FATHER: I suppose that I’ll never taste an omelet like that again.

DAUGHTER: I made the eggs just like mother always made them. If you don’t

like them, don’t eat them.

The father sips his coffee with distaste.

FATHER: The coffee is too bitter. There should be three sugars in the coffee.

DAUGHTER: I put three sugars in the coffee, no more and no less.

FATHER: These eggs are a pale imitation of your mother’s eggs. This omelet is

a sham.

DAUGHTER: For god’s sake, just eat it.

FATHER: I can’t eat it. I won’t eat it. I won’t eat your counterfeit omelet and I

won’t drink your imposter coffee.

Silence.

He eats.

DAUGHTER: Would you like part of the newspaper?

FATHER: Give me the obituaries.

She hesitates.

FATHER: Give them to me!

She hands the obituaries to her father.

FATHER: Every morning, when we read the paper, we read the obituaries

first. Did you know that?

DAUGHTER: Yes.

FATHER: Every morning, we ignored the front page. We ignored the so-

called news of the world and turned at once to the obituaries. The only news that was never out of date. The news of eternity.

He begins to open the paper to the obituaries, but closes it again.

FATHER: Your mother was always curious to learn the age of the dead, and I

was always fascinated by the means of execution—cancer, stroke, or heart attack. Your mother wanted to know precisely how old someone was when he died, to the day, and I wanted to know the exact cause of death. If the dead were younger than she was your mother would be overjoyed, and if the cause of death were suicide or murder, I’d be in a good mood for the rest of the day. Once, we came across the obituary of a nine-year old boy that had hanged himself. We were both ecstatic for a week.

DAUGHTER: I’d never seen the two of you so cheerful.

FATHER: If your mother had outlived the dead, her eyes would light up.

She would entertain herself for hours reminiscing about what she had been doing at just that age—the age of death—as she savored the taste of her morning coffee and her cigarette.

DAUGHTER: I always thought that she would kill herself with her cigarettes.

But I was wrong.

The Father again opens the obituaries, only to close them again

FATHER: We’d clip the best obituaries out of the newspaper and save them in

the filing cabinet. But only the most interesting ones. We’d only save the most ironic and the most tragic. In their photographs, in the grainy black and white photographs that they print alongside the obituaries, the dead are often smiling. There are dozens of obituaries in our collection, and now hers will join them.

DAUGHTER: There’s no reason to make things more painful than they already

are.

FATHER: There’s every reason.

Silence.

FATHER: There was always a small part of me that hoped for something else.

Each morning when I turned to the obituary section, in the moment before I opened the paper, I always thought “What if the pages are white and empty?”

He opens the obituary section.

FATHER: Here it is. Next to an ad for dishwashing soap.(He hurls the obituary section across the tbl at his daughter.) Take it, take it. I thought that I could bear it, but I can’t. I can’t read it. I can’t see it in black and white.

Silence.

The daughter opens the obituary section and peruses the pages.

DAUGHTER: At least they spelled her name right.

FATHER: At first, things are bad, and then things get worse, and then finally

things are unbearable. It’s a law of nature. I shouldn’t be surprised, but I am.

DAUGHTER: Enough. Get dressed.

FATHER: There’s no reason to rush me.

DAUGHTER: The funeral is in two hours.

FATHER: It’s absurd. A lifetime together, and in two hours we’ll say

goodbye forever.

DAUGHTER: Not forever. You’ll be together soon.

FATHER: Yes, there’s a plot reserved for me right alongside her. You’re right.

This is simply a dress rehearsal for my own funeral. A dress rehearsal for my own clumsy suicide.

The daughter begins straightening the room, collecting the piles of dirty clothes, and gathering up the old newspapers that are scattered about.

FATHER: Besides, what should I wear? What’s appropriate attire for the funeral

of one’s wife?

DAUGHTER: You’ll wear your wool suit.

FATHER: It’s the middle of August. No one wears a wool suit in August. I’ll

roast.

DAUGHTER: Your wool suit is your only black suit.

FATHER: No one wears wool in August.

DAUGHTER: Everyone wears black to a funeral.

FATHER: Why should I wear black? There’s no need to play the melancholy

Dane. “I have that inside which passes show, these but the trappings and the suits of woe.” William Shakespeare.

DAUGHTER: Don’t be ridiculous.

FATHER: I don’t care what others will think. I don’t care what they’ll say. I’ll

wear my seersucker suit. My seersucker suit is made of cotton. My seersucker suit is perfect for the August heat. Perfect for a funeral. It breathes.

DAUGHTER: You won’t wear your seersucker suit. It’s impossible to wear

anything but black to a funeral, and so black is what you’ll wear.

FATHER: It’s impossible to wear wool in August. It’s impossible to wear black

wool and stand by a grave under the August sun. I’ll sweat like a pig.

DAUGHTER: It’s impossible to wear anything but black to a funeral, and your

only black suit is made of wool. Therefore, you’ll wear black wool, and there won’t be another word about it.

She goes to the closet and removes a rumpled black wool suit.

DAUGHTER: Your pants are a disaster. You can’t go to the funeral with your

pants wrinkled like that. I’ll have to iron them.

FATHER: Don’t forget to iron my handkerchief. Who knows? I might shed a few

tears. It’s possible.

The daughter exits.

FATHER: Shouting offstage. What will you be wearing? Not that tasteless rag

that you wear to church. I forbid it.

The daughter returns with an ironing board and an iron.

DAUGHTER: I’ll be wearing mother’s black dress.

FATHER: The black dress we bought in Paris? The black dress that was always

her favorite?

DAUGHTER: Yes, the black dress.

The daughter sets up the ironing board, spreads the suit across it, and plugs in the iron.

FATHER: What will she be wearing, then? I thought that she would be buried in

the black dress, her favorite dress. The one dress that she loved more than any other.

DAUGHTER: She’ll be wearing the floral print dress. I gave the floral print dress

to the undertaken two days ago.

FATHER: The floral print is tasteless, and the black dress is perfection, and so

you’ll have her buried in the tasteless dress.

DAUGHTER: Don’t be ridiculous. The floral print dress is beautiful. It’s tasteful.

FATHER: (Disappearing into the closet.) That’s a lie. Your mother never

liked the floral print dress. Your mother loved the black dress, and she hated the floral print dress. She loved the one and she hated the other, and now you’ll bury her in the one dress that she hated most of all. You’ll bury your mother in a kitsch dress, a horrible rag.

DAUGHTER: The floral print dress was always her favorite.

FATHER: She was never so beautiful as when she wore the black dress, and

never as hideous as when she wore that kitsch floral print, covered in asinine daisies and insipid daffodils. You said yourself that one must always wear black to a funeral, that it’s impossible to wear anything else.

DAUGHTER: I said the mourners should be dressed in black. But the corpse can

wear whatever it likes. It’s too dreary, to be dressed in black for eternity. It’ll be black enough inside the coffin. It’s pitch black inside the grave. The floral print is better, more cheerful. It will brighten things up a little.

FATHER: Reemerging, wearing a white dress shirt and polka dot boxers.

Unbelievable. You want the black dress for yourself. I see right through you. You’ll walk into the funeral home wearing the black dress, proud of yourself, full of vanity.

DAUGHTER: It’s despicable to say something like that. She wasn’t just your

wife. She was my mother, too.

FATHER: You’re right, you’re right. It’s despicable, despicable is just the right

word.

DAUGHTER: Besides, the black dress cost a mint. Why dress a corpse in a

designer dress? A stupid waste.

FATHER: Yes, a stupid waste. Precisely, a stupid waste.

The father begins struggling to put on a necktie.

DAUGHTER: You should shave before you put on your tie. Otherwise, you’ll

make a mess of everything.

FATHER: I’m not shaving.

DAUGHTER: You’re not shaving?

FATHER: No.

DAUGHTER: You’ll look like a derelict.

FATHER: I’ll wear my black wool suit, if you insist, and I’ll tolerate the floral

print dress. But I’m not going to shave.

DAUGHTER: And why not?

FATHER: I don’t trust myself with a razor this morning. Every morning when I

shave, when I see the face of that miserable bastard staring back at me from the bathroom mirror, I have the urge to slit his throat. Today, I think, that urge might be too much for me.

DAUGHTER: I can’t argue with you over everything. If you insist on turning

yourself into a clown, I can’t stop you.

FATHER: Still struggling with his tie. This necktie is impossible! This necktie is

a noose! Your mother always tied the double Windsor knot for me. She straightened the tie whenever there was an important occasion, whenever there was a wedding or a funeral. Now she’s gone, and who’s going to tie my double Windsor?

DAUGHTER: Here, hold still, I’ll tie it.

The daughter sets down the iron and crosses to where the father stands in front of the mirror. She places her arms around him and ties the necktie from behind.

FATHER: How could she do this to me? How could she perpetrate this crime?

DAUGHTER: Hold still.

FATHER: You’re throttling me.

DAUGHTER: Here, here. I’ve done it.

FATHER: I can’t bear it. I can’t go through with it. Where is the rat poison?

Bring me the rat poison! I need a cup of hemlock at once!

A sudden pause.

FATHER: What’s that stench? Something’s burning.

DAUGHTER: The iron!

She crosses back to her ironing. The iron, left unattended, has burned a hole through the Father’s pants.

The Daughter holds them up to the light, revealing an iron-shaped hole in the seat of the pants.

DAUGHTER: Ruined, completely ruined. And the tailoring was the finest

money could buy, the material was the finest, 100% wool. Annihilated by my idiocy. What can you wear to the funeral now?

FATHER: No, no, it’s my fault. I distracted you with my stupid nonsense. A man

should know how to tie his own necktie. It’s unforgivable not to know how to tie a necktie. A man who can’t tie his own necktie is helpless before the world. A man who can’t tie his own necktie isn’t a man, he’s a child. A man who must depend on others for the tying of his necktie is doomed, and what’s more he should be doomed. A man who can’t tie his own necktie deserves everything he gets.

DAUGHTER: Completely destroyed. Now what will you wear? We haven’t got

time to buy you another pair.

FATHER: It’s perfectly all right. There’s no reason to cry. It’s entirely my fault,

and it’s not your fault at all.

DAUGHTER: Don’t be stupid. I’m not crying, but they’re ruined forever.

FATHER: Give them here. I’ll wear them as they are.

DAUGHTER: You can’t go to a funeral with your suit in rags.

The father snatches the pants away from his daughter.

FATHER: No, that’s exactly how I’ll go. There’s no better way to go to this

funeral than with my suit in rags.

DAUGHTER: It’s a constant humiliation to be your daughter.

FATHER: You are your mother’s daughter, too. She deserves the credit and the

blame as much as I do. And I think that you are your mother’s daughter more than mine.

The father pulls on the pants. His underwear is clearly visible through the hole in their seat.

FATHER: After all, everything beautiful in you came from your mother, and

everything ugly came from me.

DAUGHTER: I have my mother’s face, thank god.

FATHER: Not her face, but her voice. When you open your mouth, it’s always

her voice that comes out. A beautiful echo. It’s from your mother that you got your talent, not from me. Your mother had a beautiful voice, despite her tone-deaf soul. Fortunately, you have your mother’s voice and your father’s soul. Her soul was tone-deaf, and your soul is the soul of a virtuoso.

DAUGHTER: You don’t know the first thing about my soul, and you didn’t

know the first thing about mother’s soul, either. She always loved music. She loved music all her life, and that love never left her.

FATHER: A tone-deaf soul, absolutely tone-deaf.

DAUGHTER: She loved Rodgers and Haart. She loved Rodgers and

Hammerstein.

FATHER: Yes, she loved her show tunes. She loved American music, so-called

popular music. But, in America, it’s impossible to write decent music. In America, if you set out to make music, you discover at once that you can only make pseudo-music. In America, you touch the keys of a piano, fully intending to play actual music, and you automatically play nothing but pseudo-music, commercial jingles, and the theme songs of television game shows.

DAUGHTER: She would sit and play this piano all night. Singing in the Rain and Putting on the Ritz.

FATHER: How could I forget?

The Daughter sits at the piano and plays a few bars of Putting on the Ritz.The Father abruptly slams the piano shut, almost smashing his daughter’s fingers.

FATHER: Enough. I won’t hear those songs again. Now that your mother’s dead,

there’s no reason for me to suffer through those songs again. Your mother would torture me with her show tunes. She turned this piano, which was intended to be an instrument of musical expression, into an instrument of torture, an instrument of torture-expression. She would play her insipid music, and in the next room I would try to write my inspired music. But with the sound of those show tunes hovering in the air, the only music I could write was insipid music. I shouldn’t have been surprised. In Chicago, the music is always insipid, never inspired.

DAUGHTER: You haven’t written a note a years. If it wasn’t for mother, this

piano would be covered in cobwebs.

FATHER: How could I write inspired music in Chicago? To be inspired you

have to be able to breath. And I could never breath here. In Chicago, there were always hands around my throat, choking me. The air here is full of the stench of factories, the stench of slaughterhouses. Chicago is the world capital of butchers and meat-packers, and it’s the world capital of the stench that accompanies them. This city is a charnel house. In Chicago, no one can be inspired because in Chicago no one breathes. They simply gulp down air, swallow it greedily, and spit it back out. In Europe, you can breathe, and so, in Europe, you can be inspired. In Europe, you can breathe the air that Mozart breathed, and there is no air more inspiring than the air that Mozart breathed. But here, the air is enough to suffocate you. I’m suffocating, constantly suffocating.

He collapses wheezing into a chair.

DAUGHTER: Calm down. Of course you can’t breathe when you work yourself

into a state like that. Catch your breath. You’ll have a heart attack or a stroke.

Silence.

FATHER: Maybe now, with your mother gone, I’ll be able to finish my opera at

last, and at least something good will come of all this. She never supported my work.

DAUGHTER: She supported you for twenty years. Every day, she went to work,

so that every day you could sit at the piano working on your opera. Every day for twenty years.

FATHER: She may have supported me, but she never supported my work. She

loved pseudo-music, but she hated genuine music. She turned her back on genuine music. Music is useless, she said. Music won’t keep the rain off of your head. If I had been an architect, she would have supported me in every way, but I was writing an opera, and so she did everything in her power to ruin me and ruin my talent. She sabotaged everything. Your mother was an expert saboteur. Your mother always despised music. For her the only art was architecture. For her the only art was the art of keeping the rain off of your head. Your mother always loved architecture, which should have been a warning to me. A love of architecture is the true mark of a dictator and a tyrant. It’s a historical fact that the Napoleons and the Hitlers have always loved architecture. They’ve always delighted in inflicting their monumental monstrosities on the people. Always building palaces, prisons, and tombs. Your mother was just the same. Tyrants have always had architecture-addiction, they commit their political crimes, their genocides and assassinations, their wars and their executions, for the sake of being able to commit their artistic-crimes, their architecture-crimes. The Medicis loved architecture and so did your mother. Mozart loved music and so do I. That should tell you something. It’s no wonder that I’ve never finished my opera. It’s impossible for an artist to express himself under a dictatorship. A dictatorship is always intent on destroying the artist, especially if the dictatorship is a passive aggressive dictatorship of the soul. The ones who suffer the most under a dictatorship are always the artists, and your mother’s dictatorship was no exception.

The daughter rises to leave.

DAUGHTER: There’s no one left for you to fight with. I won’t do it.

She exits.

The father continues to speak to himself, seemingly oblivious to his daughter’s departure.

FATHER: If a musician plays an insipid melody, you can cover your ears. If a

violinist plays the wrong note, you can take his violin out of his hands and smash it. But an insipid building is insipid for the ages. You can’t take a tasteless building in your hands and smash it. Bad architecture is inflicted on man as a social being. It’s a crime perpetrated against humanity in perpetuity. All architects should be shot, lined up against the walls of their monstrosities and shot en masse for their crimes against aesthetics. There’s nothing worse than the desire to keep the rain off of your head. All human misery, every act of injustice and cruelty, is a direct result of wanting to keep the rain off of your head. When the last architect has been lined up against the last wall and shot, then we’ll have universal brotherhood, and not a moment before. Even the most well-meaning of them sets out to build a palace or a temple and is horrified to discover that they’ve constructed a whorehouse or a prison.

Silence.

The father looks around, as if noticing for the first time that his daughter isn’t there. After a moment, he simply continues.

FATHER: But they shouldn’t be surprised because that’s always the way and

always has been the way. This world produces one monstrosity after another and the so-called artists are no exception. In this world, the painters paint only for the blind, the writers write only for the illiterate, and the musicians play only for the deaf. Why should the architects be surprised to discover that they build their buildings for the dead? The truth is that architects never build for the living and have never built for the living but have only ever built for the dead. Every so-called masterpiece of architecture is a tomb. The pyramids of Egypt and the Tajmahal in India are tombs. The Parthenon is nothing but a sepulcher for a God long since dead, and the cathedrals of Europe are exactly the same. Your mother always wanted to be buried in a tomb. Your mother loved architecture because she always wanted to be buried in a tomb, and I despise architecture because I have always wanted to be buried in an unmarked grave. It’s as simple as that.

The father sits at the piano and plays.

FATHER: I always dreamed of returning to Europe. I knew that it was the only

place where I would be able to do my work. It was the only place capable of inspiring me. I dreamed of returning to Europe and finishing my work, but, of course, she refused the idea categorically. When I insisted on Europe she called Europe a bone yard. She called it a fascist Stalinist nightmare, a continent designed for genocide. Your mother insisted that Chicago had the best architecture in the world, better than London and Berlin, better than Paris and Rome. The supreme architecture of Europe, she said, its purest expression, is found in Auschwitz and Buchenwald. And so you mother insisted on Chicago. But when your mother insisted on Chicago, I called Chicago a slaughterhouse, a murderous city, a city designed expressly for the purpose of murder, the murder of livestock and the murder of so-called human beings, the wholesale slaughter of talent and the wholesale slaughter of ambition. Bleak, gray, dirty, infested with middlebrow atrocities waddling about in baseball caps, fat, corn-fed, unthinking. A middleclass mediocrity nightmare, every bit as awful, I said, as Europe’s fascist Stalinist nightmare, and the architecture of Auschwitz and Buchenwald, I said, is equaled in every way by the architecture of the strip malls and condominiums, those Auschwitz’s and Buchenwald’s of the soul, every bit as monstrous, and perhaps even far worse. In fact, unimaginably worse. The architecture of Auschwitz and Buchenwald was torn down and their architects went to the gallows, but the architecture of the strip malls will last for a thousand years and its architects will get off scot-free, their monstrous crimes go unpunished.

The daughter returns, wearing an elegant black dress.

FATHER: The dress.

DAUGHTER: Don’t start.

FATHER: No, no. You were right. You should take it. You should claim it as

your own. Everything that was hers is yours now. And you were right, too, that you have your mother’s face. In that dress, it’s as plain as day. Her mouth. Her expression. Her blue eyes.

DAUGHTER: Her eyes weren’t blue. They were brown.

FATHER: The first night that she wore that dress, they were performing Orpheo

at the Paris opera. The night was perfection and the performance was perfection, and I told her then, that night, that one day I would write an opera more beautiful than Orpheo and that one day she would sing it. I confessed everything to her. All of my stupid hopes. Her eyes lit up like two blue flames.

DAUGHTER: At best, you could say that her eyes were hazel. The irises had

little black flecks.

FATHER: With her voice I could have done anything. With the right instrument,

anything can be accomplished. But with the wrong instrument, nothing can be done. And her voice was the right instrument. I was sure of it. Did you know that I fell in love with her the first time I heard her sing? She was singing the part of Maria in a high school production of West Side Story. It was an abysmal production. To call it an amateur theatrical is to give it too much credit. But her voice was divine. It was only later that everything went wrong. When I met her she was simple and kind, and her voice was exactly the same. A pure expression of a pure soul. But then the soul was ruined, and the voice was ruined right along with it. Her soul became tone-deaf, and after that it didn’t matter how good her voice was. Nothing could be done with it. Everything was poisoned, and the instrument went out of tune.

The daughter begins to make the bed.

DAUGHTER: I sent flowers.

FATHER: Nothing too colorful, I hope.

DAUGHTER: Roses. Roses were her favorite.

FATHER: Lilies would be better. Something pale.

DAUGHTER: It’s time to go.

FATHER: No, not yet. We don’t want to be late, but we don’t want to be early.

For a funeral, one should always be precisely on time. Not a moment early and not a moment late.

DAUGHTER: We’ll be late.

Silence.

FATHER: Of course, your mother was never on time. Your mother was always

late. She always lagged behind the beat. The truth is that your mother always needed a conductor to wave the baton. She needed a general to tell her which way to march. She needed an editor to proofread everything she did. Her entire life needed to be thoroughly proofread by a trained professional. Her i’s dotted and her t’s crossed and every mistake circled in red. With her it was always one mistake on the heels of the next. Your mother went about everything the wrong way. Every action she took was exactly the wrong action. Every word that came out of her mouth was exactly the wrong word. Every turn she made was a wrong turn, and this is what it comes to. She taught herself German when she should have learned French. She studied philosophy when she should have studied poetry. She read Schopenhaur when she should have read Hegel. And in the end she committed suicide when she should have committed murder. One mistake after another. Even when she killed herself, she went about it in the stupidest way possible, even then everything was wrong, completely wrong. She took poison when she should have hung herself. She swallowed a mouthful of rat poison when she should have drunk hemlock. Your mother made one wrong turn after another, until she was hopelessly lost.

DAUGHTER: Arsenic does the job just as well as hemlock. Poison is just as

good as a rope. If different means arrive at the same end, what does it matter what path one takes to get there?

FATHER: No, you have it all wrong. You take too much after your mother. You

don’t understand, just as she never understood, that the end makes no difference. We all wind up at the end of a rope with a mouth full of sleeping pills and a bullet in our brain. But the methodology is the important thing. Proper methodology.

DAUGHTER: If I were going to commit suicide, I would throw myself out of a

window or jump from the top of a skyscraper.

FATHER: Jumping out of windows is for stockbrockers and superheroes. It’s not

for people like us. We die in holes, like animals.

DAUGHTER: But I’ve always heard that if you step out of a window, as the

ground rushes up to embrace you, you feel weightless, as light as air. Someday I’d like to feel that, even if only for a few seconds.

FATHER: You wouldn’t experience anything of the kind. Those last seconds

would be just as boring and unpleasant as every other moment of your life. You know that yourself, or you’d have done it long ago.

DAUGHTER: Still, it would make sense if the last thing I felt was a

disappointment.

FATHER: There are only two kinds of people, suicides and murder victims. And

everyone is one or the other. Maybe it’s too early to know which you are. Your mother was born to be a suicide, and I was born to be murdered. With your mother, it was only a matter of time until she killed herself. Anyone could see it. And with me it’s only a matter of time until I’m murdered.

DAUGHTER: There will be no shortage of suspects.

FATHER: It turned out that your mother wasn’t a true artist, despite her beautiful

voice. A true artist is never a suicide. A true artist is always murdered.

DAUGHTER: But your hero’s have always been suicides. Schumann was a

suicide. Nerval hung himself with an apron string. Van Gogh put a bullet through the brain. Even Socrates was a suicide, gulping down his cup of hemlock.

FATHER: Socrates was murdered. His philosophy forced him to drink his

hemlock. Just as Van Gogh’s paintings forced Van Gogh to put a bullet through his brain. With Schumann and Nerval it was exactly the same. Execution by suicide. The truth is an artist is always put on trial and found guilty, sentenced, and executed by his art. The obituaries will blame a stroke. They’ll diagnose heart disease or cancer. They’ll describe a so-called traffic fatality or a so-called accidental overdose, but the truth is that an artist is always assassinated by his work. A painter is assassinated by his painting, an actor is assassinated by his performance, and a philosopher is assassinated by his philosophy. Even a poem can leave a knife in your back. You put all that’s best in yourself into your work. Everything that you love. You put it into a painting, or a novel, or a symphony, and you think that, in this way, you’ll keep it safe from harm. Safe from the universal destruction. Hidden, secret, out of the reach of death. And you wake up one morning to find yourself old, helpless, and betrayed. Robbed and murdered. Your masterpiece has stolen everything and left you with nothing. You wake up one day to discover that your painting has poisoned you, that your novel has slit your throat, that your symphony is a hangman. Your masterpieces have shown you no mercy. A gang of thugs and assassins.

DAUGHTER: You’d be more convincing if you’d written a masterpiece. But

you’ve never written a masterpiece.

FATHER: Your mother tried to kill my masterpiece in self-defense. She tried to

kill it before it could finish us off. And so my masterpiece has never been completed, and maybe it never will be completed.

The father sweeps his arm across the top of the piano and sends the massive score onto the floor, scattering sheets of music everywhere.

FATHER: A lifetime of work.

He digs through the pile of music and withdraws a single sheet.

FATHER: But somewhere in this pile of trash there are seven good notes. Not

much. Still, it’s more than most accomplish in a lifetime.

Setting the sheet of music on the piano, he plays seven notes: c c g g a a g. The rhythm of these notes should be such that the fact that they are the first seven notes of “Twinkle, twinkle, little star” is somewhat disguised.

DAUGHTER: Slowly gathering up the score. The piano’s out of tune.

FATHER: Of course.

He plays the seven notes again.

FATHER: Still, I’d stack those seven notes against the world. Even if everything

else isn’t worth the paper that it’s written on. Even if everything else is shit. Those seven notes are as good as Bach or Mozart. I’m sure of it.

He plays the seven notes again.

FATHER: She’d never sing them for me. I begged her to, but she never would.

DAUGHTER: Play it again.

The Father plays the notes again.

The daughter moves to the piano.

She plays the notes again, first as her father played them, then closer to “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star.” Finally, she plays the entirety of song.

The father turns pale, and there is a long moment of silence.

DAUGHTER: It’s as good as Mozart because it is Mozart.

An uncomfortably long silence.

The father smashes the piano shut.

FATHER: How could I be so blind.

DAUGHTER: Deaf.

FATHER: What?

DAUGHTER: Deaf. Not blind.

FATHER: You’re right. I’m the one with the tone-deaf soul, and not your

mother. So perhaps I’ll finish up a suicide after all.

The father takes the score of his opera and begins tearing it to shreds.

He heaps the torn pages in a pile on the floor and fumbles in his pocket for a book of matches. Finding the matches, he strikes one and holds it over the score.

DAUGHTER: What are you doing?

FATHER: What I should have done a long time ago. Before it was too late to

save me. I’m going to burn it all. Every note. Not one of them should be spared.

He hesitates over the pile of paper until the match burns his fingers and goes out.

He strikes another.

DAUGHTER: At last, it’s happened. You’ve gone insane.

Again,the match burns his fingers and goes out.

DAUGHTER: There’s no need for this melodrama. You’ll set the house on fire.

He collapses into a chair.

FATHER: Today we’ll buy a television. This afternoon, after the funeral. We’ll

go straight to the store and buy the biggest television that we can find. It’s time to give up. It’s time to wave the white flag.

The daughter begins to pick up the books and return them to the shelves.

FATHER: If only I could be certain that it was all a joke.

Silence.

FATHER: If I were sure that it was all a joke, I’d laugh my head off.

Silence.

DAUGHTER: It’s time to go.

A long pause, in which neither of them moves.

Scene 2.

Interior of a funeral home. At one end of the stage sits an open casket, holding the corpse of the Mother. A podium stands at the front of the room, and some wretched daffodils are arranged near the casket. Several rows of empty chairs fill the remainder of the room.

Enter the Father and the Daughter. The father is wearing his black wool suit. Through the iron-shaped hole in the seat of his pants, his polka-dot underwear is clearly visible.

They stop in the doorway and look around.

FATHER: Where is everyone? Did you have the time wrong? Are we in the

wrong place?

DAUGHTER: No, this is right time. This is the right place.

FATHER: Yes, there’s the corpse, right there.

DAUGHTER: But where are the mourners?

FATHER: It’s true that she was less than popular. I’m not shocked to see that her

friends aren’t here, because her friends don’t exist. But where are her enemies? I’d have thought that there’d be scores of them here to gloat. I’d have thought that every seat would be full.

DAUGHTER: There’s no one here. No one came.

FATHER: And where are the curious? The curious are always in a hurry to

gather around a corpse, especially the corpse of a suicide. And where is her middle-class monstrosity of a family? The place should be crawling with them. I thought that they’d all come in a swarm to pick over her bones. Maybe it’s better this way, Better that there’s no one here to say goodbye.

DAUGHTER: No, this is horrible. Pathetic. Two people at her funeral. And

where’s the priest?

FATHER: Who?

DAUGHTER: The priest. Where is he? Someone needs to say a few words. I’ll

go find him.

FATHER: No, don’t leave me here alone. Let’s wait. Someone will come.

DAUGHTER: Well, let’s sit down.

The daughter walks to the front row and sits, but the father remains standing near the back of the room.

DAUGHTER: Don’t stand there like an idiot. Sit down.

The father sits in the back row.

DAUGHTER: What are you doing? Sit up here next to me.

FATHER: I’d rather sit back here.

DAUGHTER: The family should sit in the front row, I think.

FATHER: What about the stench?

DAUGHTER: What?

FATHER: From the corpse. It stinks like a ripe camembert.

DAUGHTER: Don’t be ridiculous.

FATHER: Well, if it doesn’t stink yet, it will soon. It’s sweltering in here. Don’t they have an air conditioner? Or a fan? If they kept the corpses cool, they could avoid this awful smell. But I suppose that’s why they have these flowers everywhere. To cover it up, to mask it. But they don’t fool me. They can’t pull the wool over my eyes. Ugh, I’m sweating like a pig.

DAUGHTER: It’s perfectly cool.

FATHER: You’re not wearing a wool suit. This wool suit is torture. Why did she

kill herself in the month of August? If she had killed herself in January, when the nights are long and the days are short, when the world is so cold, I wouldn’t have been surprised. Even in March, I could understand it perfectly. The winters are long. They make people miserable and hopeless. People kill themselves in droves in the month of January and in the month of March. But there’s no reason in the world to kill oneself in August.

Silence.

DAUGHTER: Take off your jacket, then.

FATHER: There’s only one conclusion that I can draw. I’m absolutely certain

that she killed herself in August on purpose, that she deliberately chose the hottest time of the year, because she knew that my only black suit was made of English wool. This wool suit is torture. It’s deliberate, premeditated torture.

DAUGHTER: Take off your jacket.

Silence, in which the father does not remove his jacket.

DAUGHTER: And so there will be just the two of us. A disaster. I thought that

the neighbors would be here, at least. She got along well with the neighbors.

FATHER: Yes, I was sure that the neighbors would be here to gloat and gossip.

Now that she’s dead the neighbors’ tongues won’t stop wagging. They always suspected and now they have proof. Your mother was a madwoman.

DAUGHTER: She was an idealist. That was something that they could never

understand, and neither could you.

FATHER: Well, the truth is that your mother was both an idealist and a

madwoman. Whether she was an idealist first and went mad, or was a madwoman first and then developed ideals, is impossible to say and makes no difference. All idealists are insane, and the insane are always idealists. They each carry something around inside their skulls that no one else understands. They carry a burden that no one else carries. Your mother was from a long line of idealists and lunatics. Like all idealists, she was sickeningly sentimental about humanity. She wept tears over humanity. I’ve seen her do it more than once. And, like all idealists, she hated human beings. She was dismayed to find herself always confronted with human beings, and never with humanity. Unlike your mother, I’ve always hated humanity. I’m not sentimental. If I could get my hands around the throat of humanity I’d strangle it. Humanity’s crimes are colossal and deserve nothing less than capital punishment. But, unlike your mother, I like human beings.

DAUGHTER: That’s a lie.

FATHER: It’s the truth. I have the deepest sympathy for them. At least for one or

two of them. I’m fond of Shakespeare. I’m fond of Bach and Mozart and Brahms and Beethoven. I’m practically overflowing with goodwill toward my fellow man. And the truth is that I was fond of your mother, and I’m fond of you.

The daughter rises and goes to sit beside her father.

FATHER: I suppose that I’m glad that it’s only us here today. It’s better this

way. I couldn’t bear to see a stranger’s face.

They sit in silence for a few moments.

FATHER: The flowers look wretched, of course.

DAUGHTER: They smell nice.

FATHER: They barely cover the stench.

DAUGHTER: How she ever fell in love with you is a mystery.

FATHER: A mystery to me more than anyone. The one true blessing of my life.

DAUGHTER: And my curse. The two of you dragged me into this world against

my will. I’ll never forgive you for it.

FATHER: I can’t take credit for your birth, and I’ll take no blame. Your mother

deserves the credit and the blame. She’s the one who plotted your birth. She’s was the chief-conspirator. I was only the flunky, the patsy. I was a victim, just as much as you were a victim. We were both victims of your mother’s childbirth plot, her motherhood plot.

DAUGHTER: Why someone who was so unhappy would ever bring another

creature into this world is something I could never understand.

FATHER: Your mother thought that she was plotting an escape. She thought that

a child would be a way out of the trap. She thought that she was digging an escape tunnel in the form of a child. She thought that together she and I might bring some beauty into the world. She thought that beauty might save us both. A ladder, she thought, would be let down from heaven.

DAUGHTER: She was wrong.

FATHER: Completely wrong. Children are little monsters. Children are nothing

but shrill voices and murderous little hands. But at least you had a happy childhood.

DAUGHTER: Happy? Every night we sat at the dinner tbl, eating off of the

good china. You would sit on my left-hand side, and mother would sit on my right, and you would attack me from the left and mother would attack me from the right, like Scylla and Charybdis. You would question me about music and mother would question me about architecture. You would attack me with music and she would attack me with architecture.

FATHER: We educated you.

DAUGHTER: You crippled me.

FATHER: We nurtured you.

DAUGHTER: You tortured me.

FATHER: We spoiled you.

DAUGHTER: I wasn’t allowed to do anything that a normal child was allowed

to do.

FATHER: Ridiculous. Name one thing that we refused you.

DAUGHTER: We never went to the zoo.

FATHER: The zoo? The zoo is an awful place. You should thank me for never

taking you there. When I was a little boy my parents dragged me to the zoo, and it was one of the worst experiences of my life. I walked through the miserable cages, and the monkeys stared back at me with looks of contempt. The lions and the tigers watched me with eyes full of disgust. The zoo is an unbearable place.

DAUGHTER: I’d like to see a lion. A lion or a monkey. Even in a cage. I don’t

think they’d look at me with contempt or disgust. They’d give me a look of recognition, a look of sympathy. I’ve lived my whole life in a cage, and so have they.

FATHER: Don’t exaggerate.

DAUGHTER: I didn’t grow up in a family. I grew up in the ruins of a family.

FATHER: Well, we tried to make you happy. But I suppose it was hopeless from

the start.

DAUGHTER: At least I won’t be guilty of inflicting life on a child.

FATHER: Your existence wasn’t my idea. I remember when your mother told

me that she was pregnant. I was furious. After all, it isn’t just the Hitlers and the Stalins who are guilty of mass murder. Those who procreate the species, those who feed their vanity and fight their loneliness by bringing another victim into the world, sentencing an innocent to suffer and die, are committing the greatest crime that can be committed. Don’t worry. I made my feelings on the matter clear. But your mother insisted. She couldn’t be dissuaded from her plot.

DAUGHTER: Everyone wants someone to keep them company in their

misery, someone to outlive them. But when they’re gone the child is always left alone, terrified, frightened, standing on the gallows by themselves. Every child that’s born is sentenced from birth to torture and death, en masse. I’m no exception.

Silence.

FATHER: Your mother thought that a child would be a way out of our marriage-

trap, just as she thought that our marriage would be a way out of her father-trap. She thought that she was digging an escape tunnel, but she was only digging a grave, and that’s always the way. You think that you’re digging an escape tunnel. You burrow and you burrow. Your lovers, your family, your children, your art. You think that each of them is a tunnel to freedom, a way out of the ugly trap, under the barbed wire to reach the blue sky, but each tunnel collapses, one after the other. You think that you’re digging an escape tunnel, but you’re only digging a grave, shallow, horribly shallow, despite the awful long years of effort, barely deep enough to cover the stench.

DAUGHTER: The coffin is smaller than I thought it would be.

Silence.

FATHER: But your mother was beautiful on our wedding day. She glided down

the aisle like a swan. Her long white throat was like the throat of a swan. I’d never seen her so beautiful, and I suspected then that I’d never see her so beautiful again. I wanted to put out my eyes, like Oedipus, so that the last sight I would ever see would be your mother, young and beautiful and happy.

Silence.

DAUGHTER: Where is the priest? I can’t take much more waiting.

FATHER: And I would have been right to put out my eyes. They would have

hauled me off to the madhouse but it would have been the sanest thing that I could have done. Because she never looked so beautiful again. Never so young and never so happy. Her beauty began to fade at once, and her happiness too. But by then it was too late. Too late for her and too late for me.

DAUGHTER: Why she married you, I can’t understand. A third-rate music

teacher.

FATHER: I was a first-rate music teacher. My students loved me. Your mother

wasn’t the only one. I was voted teacher of the year for three years in a row. I have plaques hanging on the wall. I have plaques.

DAUGHTER: I know. I polish them every day.

FATHER: Of course, no one approved. Her father was dead set against it. Her

mother called it a catastrophe in the making. They were both right, of course, but I wouldn’t be stopped, and she wouldn’t listen. I gave her daffodils and played the piano, I told her about Mozart and Bach. I recited Tennyson and Wordsworth. I brought her books to read and she devoured them. Before we were married, everyone insisted that I was after her fortune. They assured her that I couldn’t wait to lay my hands on it. But she knew me better than they did. She knew I didn’t have the least interest in her fortune. I was hungry for her soul. I thought that it would be a tasty morsel. I smacked her lips over it. Little did I know that it was thoroughly laced with arsenic.

DAUGHTER: Don’t.

FATHER: The truth is that I thought that marrying your mother would have a good effect on me. Before I married your mother, I was a beast. I was ruled by my passions. I was debased, a sensualist, consumed with lust. I was convinced that marriage was a necessary step in the development of my character.

DAUGHTER: Before you married her, you were debased, a sensualist, and

consumed with lust. After you married her, you were debased, a sensualist, and consumed with lust. But now you were also hypocritical. For you, this is what passes for character development.

FATHER: Well, everyone develops their character in their own way. For me,

character development meant marriage. For your mother, character development meant her psychoanalysis and her little pills. Her doctor. That quack. That fraud. That Mengele.

DAUGHTER: You can’t blame her psychiatrist for what happened.

FATHER: I admit that he had an impossible task. Your mother always lived in a

bunker, a bunker inside her skull. For your mother the Russians were always at the city gates, and the bombs were always falling. Your mother’s mind was always a bomb-shelter mind, Her mentality was always a bunker-mentality, a last-stand mentality, she was always fighting a desperate, last-ditch defense against the world. A hopeless defense.

DAUGHTER: Still, if someone had told me that one of you would commit

suicide, I would have guessed that you would have been the one and not her. She was always the strong one and you were the weak one. But maybe it takes strength and not weakness.

FATHER: It doesn’t take strength and it doesn’t take weakness. Love is the only

requirement. One only murders what one loves.

DAUGHTER: Do you think that’s true?

FATHER: You destroy what you love because the thing that you love seems to

have something precious hidden inside of it. A secret that you can’t understand. So you destroy the one you love to reach the secret hidden inside. You cut the body open to clutch the heart.

Silence.

DAUGHTER: It makes no sense.

FATHER: Your mother loved herself too much. And so she broke herself into

pieces to get at the toy prize hidden inside. I, on the other hand, despise myself too much to want to see what’s at the heart of this ugly, misshapen thing. Suicide is narcissistic, performed out of self-love and self-pity. An attempt to end the pain of a creature in agony. An act of mercy. And that’s why it’s inhuman.

DAUGHTER: The desire to destroy oneself seems perfectly human to me.

FATHER: It’s inhuman to be so merciful towards oneself. After all, it isn’t

rationality that makes someone human. It isn’t the knowledge of good and evil that raises him above the animals. Man is the only creature who can despise himself. It is his capacity for self-loathing that makes someone fully human. And I am nothing if not fully, miserably human.

Silence.

FATHER: Look at that.

DAUGHTER: Look at what?

FATHER: There’s a smile on her face. They’ve put a smile on her face, in the

most unnatural manner. Completely unnatural. The miserable way they treat the body in these places, dressing them up like dolls, powdering their faces, parading them about. A funeral is nothing but one long travesty, one long insult to the dead. They say that a funeral is to honor the dead, and then they proceed to molest the corpse, to treat the corpse like a puppet or a rag doll. They’ve put a smile on her face, do you see it?

DAUGHTER: I see it.

FATHER: Her face shouldn’t be wearing a smile, she never wore a smile. Her

expression was always an expression of disappointment. Never a smile, always a frown. They’ve disfigured her. They’ve mutilated her beyond belief.

DAUGHTER: It’s customary. It makes the body seem more cheerful.

FATHER: This is impossible. This is unbearable.

DAUGHTER: Calm yourself.

FATHER: No, I won’t calm myself. Look at her, grinning like an idiot. In life,

she never grinned like an idiot. Why should she grin like an idiot in death? At most, she smirked, and occasionally she sneered, but I can say with absolute certainty that I never saw her smile. She’s virtually unrecognizable like that. If they buried her with a smirk on her face, or with her lips twisted into a sneer, I could bear it. But that is a smile on her face. Her lips are twisted into a smile, I’m sure of it.

DAUGHTER: I think that it could be a smirk. It’s difficult to tell in this light, and

at this angle, but I think that it might be a smirk.

FATHER: Stop it, stop it. Stop trying to placate me with your lies.

The father rises from his seat and moves to the casket, peering intently at the face of the corpse.

FATHER: That is a smile. That is no smirk. I know a smile when I see one, and

they’ve inflicted a smile on her corpse. It’s as plain as day.

DAUGHTER: Well, so what if they have?

FATHER: It’s undignified.

DAUGHTER: Another indignity, after a lifetime of indignity.

FATHER: But the corpse should be treated with dignity. Even if the corpse has

never been treated with dignity in life, in death, the corpse should be treated with dignity. If a corpse should be treated with dignity anywhere, it is at the funeral. They can’t put her in the grave like that. I won’t allow it. She shouldn’t be forced to grin like an idiot through eternity.

DAUGHTER: What difference could it possibly make if they bury Mother with a

smile on her face? When the flesh is gone and only the skull is left, the skull will grin. We’re all forced to grin like idiots in the end.

FATHER: No, I won’t have it. I won’t allow it.

He reaches into the coffin and changes the smile on the face of his wife’s corpse to a frown.

DAUGHTER: Don’t touch her.

The father returns to his seat.

FATHER: That’s better, that’s better. A proper frown on her face.

Silence.

DAUGHTER: How could you do that?

FATHER: The body should be treated with respect, and instead they treat it with

nothing but disrespect. It’s vile, utterly vile. Of course, the way they treat the body is nothing compared to the way they treat the soul. Every humiliation they visit on the body, is visited on the soul a hundred-fold. For every insult they deliver to the body, they deliver a hundred insults to the soul. Every tasteless indignity inflicted on the body of the dead, of which there are no shortage, is replicated one hundred times over on the soul of the dead.

DAUGHTER: This is a disaster. I can’t take this any longer. Where is that priest?

She rises.

FATHER: Sit down. There won’t be a priest.

She sits.

FATHER: When he came to see me last week, I told him that his services would

not be required.

DAUGHTER: What?

FATHER: We don’t have any use for a priest.

DAUGHTER: But you can’t have a funeral without one.

FATHER: That priest was a fraud, I’m sure of it. He’d have stood over her body

dispensing platitudes and panaceas. What does he know about grief? I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that he’d never read Ecclesiastes. I can’t imagine the drivel that would have come out of his mouth. The affronts and insults. That priest was a hired lackey, a mercenary mourner, interested only in collecting his fee, his thirty pieces of silver. A vulture circling the corpse. And so I chased him away.

DAUGHTER: A deliberate act of sabotage. A funeral without a priest.

FATHER: That priest wasn’t competent to officiate at the funeral of a family pet,

much less the funeral of a so-called human being. We’d have sat and listened patiently while he heaped insult after insult on her, in the guise of praising her. It would have been too much, too much. Grotesque.

DAUGHTER: Someone has to speak. There have to be words.

FATHER: What is there to say? If someone kills themselves at eighteen or

twenty, everyone knows what to say. “What a tragedy! What a loss! What a waste!” When someone kills themselves at her age, people can only shrug their shoulders and say “What took her so long? It’s been clear for years that her life was a botched job.”

DAUGHTER: Don’t.

FATHER: No, it’s pathetic to commit suicide at such an advanced age. Of

course, it’s absurd to live to such an advanced age in the first place. Whenever I see an old man or an old woman, I’m immediately suspicious. In a world like this one, it’s suspicious to survive for too long. Old age is a sure sign of a villainous nature. With every year that goes by, you commit another crime.

DAUGHTER: She was innocent.

FATHER: I always suspected that she’d be her own executioner. But she waited

too long, of course. Always doing everything at the wrong time. Always late. Always out of tune. Of course, in this world everything is always done too late. Nothing is ever done at the right time. Only in music, when music is played properly, and, in this world, music is never played properly. If a tune is supposed to be played in 4/4 time, we play it like a waltz. If the band plays a waltz, we dance a polka. In this world, a musical disaster is guaranteed, no matter what.

Silence.

FATHER: I had high hopes for you once. Do you remember the songbird I bought for you?

DAUGHTER: The canary.

FATHER: You had such a beautiful voice. Even when you were a baby, the sound of your crying was beautiful. Your mother wanted you to be an architect. She wanted to put you to work building prisons and tombs. But I always thought that one day you would be a star on the operatic stage. Your voice was angelic.

DAUGHTER: You always loved my voice more than you loved me, just as you loved mother’s voice more than her.

FATHER: I bought you a songbird and hung it in a cage in your room because I wanted you to always be surrounded by beautiful music.

DAUGHTER: Constant screeching and insipid twittering.

FATHER: I thought that its melodious voice might inspire you. One day, I

thought, she’ll be a star on the operatic stage. A world-class soprano. And this songbird will instill in her a love for all things musical. And then one night you snatched it out of its cage and smothered it with a pillow. I was horrified. Your mother was delighted, but I was horrified.

DAUGHTER: I thought that it would please you when I smothered the songbird.

FATHER: How could it please me? A crime like that. A crime against Mozart.

DAUGHTER: You always taught me that the mark of a true artist is a lust for the

blood of one’s rival.

FATHER: You were endowed with undeniable talent, and all of your talent has

come to nothing. All that was required was effort. Practice and dedication. Patience. And instead you threw everything away. You destroyed everything.

DAUGHTER: I was always jealous of the person I was supposed to become. It

sounds stupid to say it, but I hated her. I was the one who would have to pay the price. I was the one who would have to sacrifice everything, suffer every humiliation, and make every mistake. And that other me, that future me, that person that I was sacrificing everything to become… she would reap the rewards and claim the glory. My soprano was laughable and hers would be perfection. Should I spend every afternoon singing scales for her sake? Everyone loved her. No one loved me. It was unfair. And so I murdered my future in cold-blood. I poisoned it.

Silence.

DAUGHTER: Don’t look so shocked. It was an act of self-defense. If I hadn’t

murdered my future, my future would have murdered me. It plotted my destruction, but I was too clever for it. I outwitted it. It’s true that I despise the person that I’ve become, but I despise even more the person that I might have become.

FATHER: You poisoned her.

Silence.

DAUGHTER: She asked. Not with her mouth, but with her eyes. Her eyes

begged. Her eyes had begged for a very long time. And so I went to the hardware store and I told them that I needed to kill a rat. They gave me arsenic in little white tblts and the told me how to use it. They gave me very clear instructions. I mixed it with her coffee in the morning. I mixed it with her coffee in the morning and when I gave it to her she complained that it was too bitter, even though I put in three extra lumps of sugar. But I could tell that when I gave her the poison, she was grateful. Her eyes were grateful. It took ten minutes. I sat next to her and I watched the clock ticking away the seconds. First her fingers grew numb. Her limbs grew heavy. Drowsiness overtook her. It was a tremendous sensation, to feel the pulse, the beat of the blood, growing slower, and slower, and then stopping. And then nothing more. An empty room. It was suddenly so quiet.

Silence.

FATHER: Ten minutes. Life is too long.

DAUGHTER: For some.

Silence.

FATHER: I always thought that when I finished my opera…

DAUGHTER: If you finished your opera.

FATHER: …that if I finished my opera, your mother would be the one to sing it.

The truth is that I was writing it expressly for her, for her voice and for her soul. And that is precisely why she never allowed me to finish it.

DAUGHTER: I don’t understand.

FATHER: I don’t understand myself.

Silence.

DAUGHTER: I suppose that no one else is coming after all.

FATHER: I suppose not.

DAUGHTER: Say something.

FATHER: What can I say?

DAUGHTER: Someone has to say something. The eulogy.

FATHER: Yes, someone should speak. Someone should deliver the eulogy.

He rises from his chair and stands at the podium.

FATHER: I can’t do it.

He returns to his seat, and then abruptly stands again.

FATHER: I can’t do this alone.

DAUGHTER: I know.

The father sits once again.

FATHER: The world treats all of us horribly. Everyone suffers. It isn’t fair.

DAUGHTER: The world is badly made. But maybe it’s right that people suffer.

Maybe they only get what they deserve.

FATHER: No, that isn’t what I mean. It’s not the fact that they suffer that’s

unfair. What’s unfair is that everyone else’s suffering makes my suffering feel trite.

Silence.

FATHER: I’ve always been interested in death. But never in heaven or hell. My

curiosity has always stopped at the edge of the grave. But the thought that I will never see your mother again is inconceivable. It simply can’t be.

After a long moment of silence, he suddenly begins speaking.

FATHER: Maybe your mother is right. Maybe there’s no other way out. Maybe

it’s necessary to put yourself in a coffin if you want to give yourself time to think. She was right to close herself off in a coffin. She was right to bury herself in a grave. There’s no other way. But I don’t know how I’ll survive without her. No one can survive alone. Everyone needs a victim, a fool to mock, an innocent to torture. The truth is that whenever people are together one is always turned into a victim and a laughing stock. Your mother knew that better than anyone. Someone is always handed the dunce cap and made to go sit in the corner with their face to the wall. Always the weakest among us is given the heaviest burden, made to drag the heaviest burden limping through the streets, made to drag the heaviest burden to the place of execution

Silence.

DAUGHTER: Go on.

Silence.

FATHER: I can’t go on. I can’t go on any more. I’m sick of words.

The father sobs silently.

DAUGHTER: You can go on. And you will.

FATHER: It’s useless.

Silence.

FATHER: When I was young my father sent me to Europe to study music. My

father sent me to Europe to study music in the most musical country in the world, the land of Mozart, among the most musical people in the world, the people of Europe. Of course, I despised the music academy. I despised Europe. I hated being alone, far away from everything that I had ever known. I was lonely, wretched, and miserable.

Silence.

FATHER: Can I tell you a secret? When I was young, I despised music. When I

was young, there was nothing I hated so much as music and no one I hated so much as Mozart.

Silence.

FATHER: But one night, in the middle of December, the musical academy

caught fire. It was a dilapidated old fire trap. It went up like it was made of matchsticks, and of course there were no fire escapes. It was only because I’ve always been lucky that I managed to escape alive. I stood outside, on the cobblestone streets, shivering and frightened, and I listened to the flames consume the building. And then the strangest thing happened. It was a terrible piece of architecture. Dark and cramped and oppressive. A death trap. But as the fire consumed it, it ceased to be a building. It became a symphony. I stood freezing on the street outside, and I listened to the music of the snapping piano strings and the screams of my fellow students, trapped inside, and it was the most beautiful sound that I had ever heard. It made the music of Mozart and Bach seem insipid. And I fell in love with music on that night. Ever since that moment, I’ve dreamed of composing something as beautiful as the music I heard on that night. And when I met your mother, when I heard your mother’s voice, when I heard your mother sing for the first time, when I heard her sing in a high school auditorium, standing in front of a cardboard set, I knew that this was the voice that could sing the music that I heard in my head. It would require patience, a slow cultivation over long years, a careful nurturing. I would have to feed that voice a steady diet of suffering, each that soul to feast on agony. Because I knew that the music I heard in my head would require, above all else, the voice of a soul in great torment. With each year that passed her voice became more beautiful, more sublime, more saturated with pain. And she submitted herself willingly. She gave herself over to me. She let herself be martyred for the sake of beauty.

Silence.

FATHER: think that she loved me.

Silence.

FATHER: But now I see that my pedagogical methods were unsound. Now I see

that I may have miscalculated. And now everything is lost.

DAUGHTER: You don’t know what you’re saying. You’re out of your mind

with grief.

FATHER: So what if I am grieving? I have the right to grieve. Everything is

over, everything is lost. I know just what I’m saying. I’m speaking the truth, the only the time anyone says anything that isn’t a lie is when they’re crippled, when they’re broken, and then they can’t shut up. I don’t understand how it came to this. I‘m not surprised that it came to this, but I don’t understand it, I can’t understand it, and I won’t understand it.

The Mother, still lying in the coffin, eyes closed and otherwise motionless, begins to sing the first seven notes of Twinkle Twinkle Little Star. At first there is only a low, almost inaudible hum. Throughout the rest of the scene, she repeats the passage three times, gradually louder, at last singing at full voice. The rhythm and length of the notes slowly transform on each repetition into the Father’s seven notes.

The father is transfixed; the daughter, oblivious.

FATHER: Do you hear it?

DAUGHTER: Do I hear what?

FATHER: Shhhh… Didn’t you hear it? Her voice. She sang.

DAUGHTER: I didn’t hear anything.

The Mother sings for the second time.

FATHER: There… again.

DAUGHTER: I can’t hear anything. There’s nothing to hear. She’s dead, Father.

She’s dead.

The mother sings for the third and final time.

As she sings, the Father begins to sing as well.

When the last note dies away, there is a long moment of silence.

CURTAIN

следующая Ника СКАНДИАКА. СТИХИ

оглавление

предыдущая Rafael LEVCHIN, Anatol' STEPANENKO. COLLAGES OF FORTY-YEAR-OLDS

blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah

πτ

18+

(ↄ) 1999–2024 Полутона

(ↄ) 1999–2024 Полутона

Поддержать проект

Юmoney